|

|

|||

| The Trafalgar Campaign: The Long Blockade of Toulon |

| (This Page) The Trafalgar Campaign: The Chase of Villeneuve |

| The Trafalgar Campaign: Countdown to the Battle |

| Trafalgar: Nelson's Final Battle |

| The Death of the Hero |

| Trafalgar: The Aftermath and the Hurricane |

The Trafalgar Campaign: The Chase of Villeneuve

Throughout 1804 and 1805, the British Prime Minister, William Pitt, set about forming a coalition between Britain, Russia and Austria against France. Initially, Austria were cautious, as their position in Europe, so close to Napoleon's dominions, made them vulnerable, and they had been defeated by him before. But they were keen on revenge, and joined the coalition soon after Russia. Russia and Britain did not trust each other, but Russia dominated the Baltic, from where Brtain got supplies that were valuable to the Navy. However, Russia was concerned about the threat to its Mediterranean interests from France.

Eventually, the British government agreed to send troops to join the Russians in Italy, as well as secure Sicily, Naples, Sardinia and Alexandria. This pleased Nelson, and went some way towards easing his concern about those places.

Napoleon realised he had to act soon, but his problem was that he did not understand naval warfare at all - his plans didn't take into account the effects of weather, currents and bad communication at sea. His tendency to wildly change his mind didn't help matters, and neither did his inability to accept advice from his Minister of the Marine. His options were to invade England, or to persuade them to make peace. Invasion looked increasingly less likely - he knew the strength of England's defences and their Channel Fleet, and he was also aware that he wouldn't be able to have his whole invasion force cross the Channel in one go, due to a lack of transport.

Napoleon famously called Britain 'a nation of shopkeepers', and knew that if he couldn't invade them directly, he'd have to attack their dominance over sea trade in order to threaten them. He planned for his fleets at Toulon, Brest and Cadiz to join with the Spanish and go to the West Indies to attack British trade there, before returning to Europe. He also thought that part of his fleet could go north, around Scotland and back down to the Baltic, and part of the fleet would go to Brest; together, they would surround the British Channel Fleet and pose a significant threat. However, while this may have worked very well on land, it could not work at sea. It also relied on there being no battles, and did not account for the fact that the British were not afraid to fight, and would only allow themselves to fall back on the defence of the Channel as an absolute last resort.

In

August 1804, the French Admiral Latouche-Treville was climbing the hill from

which he could see the English ships, as he had done every day since he'd

arrived at Toulon, when he suffered a heart attack and died. He was

59. Napoleon replaced him with Vice Admiral Pierre-Charles-Jean-Baptiste-Silvestre

de Villeneuve (bit of a mouthful!). Possibly no French Admiral had

more reason to wish to fight Nelson than he - or, for the same reason, to

fear him.

In

August 1804, the French Admiral Latouche-Treville was climbing the hill from

which he could see the English ships, as he had done every day since he'd

arrived at Toulon, when he suffered a heart attack and died. He was

59. Napoleon replaced him with Vice Admiral Pierre-Charles-Jean-Baptiste-Silvestre

de Villeneuve (bit of a mouthful!). Possibly no French Admiral had

more reason to wish to fight Nelson than he - or, for the same reason, to

fear him.

Villeneuve had commanded the rear division of the French fleet at the Battle of the Nile. In the end, and after having no particularly noticeable impact on the battle, he escaped on his ship, the Guillaume-Tell, with just one other ship, the Généreux, and two frigates (incidently, the Guillaume-Tell and Généreux were both later captured by the English, the latter by Nelson, to his immense satisfaction). With his only achievement being escaping from the Nile, Villeneuve was not much respected, even by Napoleon, who thought he was a coward.

In January 1805, Napoleon decided it was time to attack the British in the West Indies, drawing the British fleet away from Europe. So he ordered Villeneuve, and Rear-Admiral Missiessy, who had six ships-of-the-line at the port of Rochefort, to take troops with them to do just that. On the 11th of January, Missiessy managed to escape the British blockade and escaped into the Atlantic, with the British Rear-Admiral Alexander Cochrane in hot pursuit.

On the 18th of January 1805, Villeneuve decided to make his move. Nelson was anchored at Agincourt Sound at the time, some way to the south-east from Toulon, and so Villeneuve slipped past him. The frigates that Nelson had left to watch Toulon, the Seahorse and Active, ran to tell Nelson what had happened. But that left no British ships tracking Villeneuve's movements. As usual, Nelson believed the French would attack one of the eastern Mediterranean countries - Sardinia, Naples, Malta or Egypt - and so he rushed south, thinking he could intercept them on their way. A week later, and still with no sign of the French and no intelligence whatsoever as to where they could have gone, Nelson took a chance and headed eastward, leaving cover at Naples and Sicily just in case they turned up there. But they weren't at Alexandria, and when he called at Malta on the way back to the west, he heard that they were back in Toulon.

Villeneuve hadn't got very far. The storms that Nelson and his fleet had weathered for two years battered the French ships on their first night out, and they were forced to limp back to Toulon to repair and wait for better weather. By the end of February, Nelson had returned to his familiar haunt, relieved that the French hadn't escaped from him, but continually frustrated by his lack of 'eyes' to watch them and angrily, bitterly and often complained it about to almost everyone he wrote to.

As for Missiessy - he continued to run around the West Indies, chased by Cochrane, until news of Villeneuve's failure reached Napoleon, and he recalled him.

By March 1805, Nelson hadn't heard a word from the Admiralty since November the previous year - a dispatch ship had been caught by the French. He was exhausted, ill, and wanted to go home. So he finally resolved that enough was enough, and developed his own plan to initiate a battle.

Nelson went west to Barcelona, and waited there long enough that he knew his whereabouts would be reported to Villeneuve. He then ran back south-east to Sardinia, and waited. He hoped to trick Villeneuve into thinking he could avoid the British by heading east, but would instead run into his trap.

And it almost worked. Villeneuve did indeed start towards the east, and would indeed have sailed right into Nelson's trap. But disaster struck as he ran into a neutral ship, which gave away Nelson's true position. So Villeneuve veered to the west, and ran off to join the Spanish instead. The two frigates shadowing the French fleet lost sight of them, and by the time Nelson realised what had happened, he had no idea where they had gone. But rather than make the mistake of charging off somewhere, he spread his fleet between Sardinia and Tunisia, so if the French doubled-back, they wouldn't get very far.

Villeneuve hurried to Cartegena to

collect the Spanish ships there, but they would not join him until they had

orders from Madrid. Knowing that Nelson would be hot on his heels, Villeneuve

didn't hang around, and took off. He sped through the Strait of

Gibraltar. A small British squadron commanded by John Orde waited

there, but rather than fight them, he let them pass, and sent warnings to

Nelson, the West Indies, and the Grand Fleet that was sitting up near

England. He probably assumed that Nelson would be on their tail, but

the next day, with no sign of any of Nelson's squadron, Orde sent a couple

of ships after Villeneuve, but they lost him. From Cadiz, he picked up

one French ship-of-the-line, and six Spanish under Admiral Federico Gravina,

and they disappeared into the Atlantic.

from Madrid. Knowing that Nelson would be hot on his heels, Villeneuve

didn't hang around, and took off. He sped through the Strait of

Gibraltar. A small British squadron commanded by John Orde waited

there, but rather than fight them, he let them pass, and sent warnings to

Nelson, the West Indies, and the Grand Fleet that was sitting up near

England. He probably assumed that Nelson would be on their tail, but

the next day, with no sign of any of Nelson's squadron, Orde sent a couple

of ships after Villeneuve, but they lost him. From Cadiz, he picked up

one French ship-of-the-line, and six Spanish under Admiral Federico Gravina,

and they disappeared into the Atlantic.

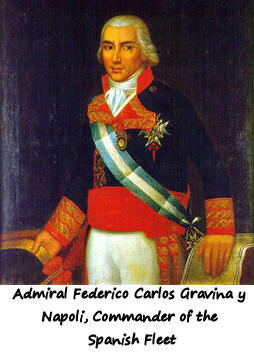

Gravina had distinguished himself by playing a major part in the negotiations between Spain and France, as the Spanish Ambassador to France. As a reward, he was made Commander-in-Chief of the Spanish Navy. He was never confident of Villeneuve's leadership, and wasn't happy at being placed under him.

Meanwhile, Nelson had heard of Villeneuve's escape but was frustratingly trapped at Sardinia for five days due to the stormy weather. Eventually, he managed to set off to the west, but gloomily decided that if he heard no definite news of where the French had gone, he would have to head back to the Channel to help the fleet there to defend, as the likelihood of managing to catch the enemy in the vast open water of the Atlantic before they got back to England, was slim.

Eventually, in May, Nelson reached Gibraltar and stocked up on supplies in preparation for a long chase. He was not afraid of the prospect of a long voyage, nor of the fact that, with the addition of the Spanish ships to Villeneuve's fleet, he was badly outnumbered.

With the little intelligence that Orde's ships could give him, along with his own intuition, Nelson was convinced that Villeneuve was heading for the West Indies. In his absence, Vice-Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood, his long-time friend, was sent to tightly blockade Cadiz and other enemy ports in the Mediterranean. By now, all the major French and Spanish squadrons were blockaded in, and only Nelson and Villeneuve were on the move.

Nine French and Dutch ships were trapped in the Netherlands by Admiral Keith's eleven ships.

Admiral William Cornwallis' fifteen ships patrolled the Channel as far as the Irish coast, as a last line of defence, and effectively blockading Vice-Admiral Joseph Ganteaume's twenty-one ships at Brest.

Rear-Admiral Thomas Graves had five ships blockading the four enemy ships at Rochefort.

Vice-Admiral Robert Calder had eight ships outside Ferrol, keeping in check four French ships under Rear-Admiral Gourdon, and eight Spanish under Admiral Grandallana.

Napoleon

wanted Ganteaume's large Brest fleet to take troops to Ferrol, put Calder's

blockading squadron out of action, then go with Gourdon and Grandallana's

fleets to Martinique in the West Indies where they would meet with

Villeneuve. The massive combined fleet, by then consisting of 44

ships, would return to the Channel, crush any British resistance, and allow

the French army to cross the Channel in safety.

Napoleon

wanted Ganteaume's large Brest fleet to take troops to Ferrol, put Calder's

blockading squadron out of action, then go with Gourdon and Grandallana's

fleets to Martinique in the West Indies where they would meet with

Villeneuve. The massive combined fleet, by then consisting of 44

ships, would return to the Channel, crush any British resistance, and allow

the French army to cross the Channel in safety.

But the British blockades, particularly of Ganteaume's large fleet, was a massive blow to the plan.

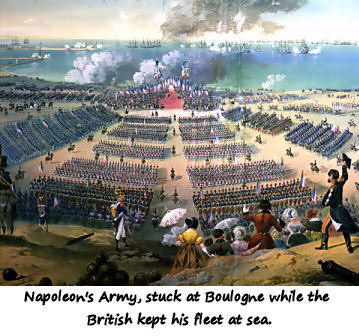

So Napoleon and his large army intended to invade England, were still embarrassingly stuck at Boulogne.

Nelson was, as in the chase leading up to the Battle of the Nile, a victim of his own eagerness, and got to the West Indies ten days before Villeneuve. There, he met with one of Cochrane's ships left behind after he had chased Missiessy, giving him a total of 12 ships against Villeneuve's 18. Nelson asked around for intelligence, and was told by a British General that Villeneuve's fleet had been seen going south towards Trinidad with a large army. Nelson's own intuition told him that the enemy would have gone north, but he reluctantly took the intelligence to be reliable, and took troops southwards.

Nelson fully expected to find the French fleet at anchor with troops ashore, trapped as they had been at the Nile, and he issued battle orders to that effect. But they were not there. Villeneuve had indeed gone to Martinique, further north, and waited for Ganteaume, not knowing that he was still stuck at Brest - and, whilst there, had pointlessly captured the tiny British-occupied Diamond Rock.

Nelson later, in a letter, quite rightly raged at having been given bad intelligence, when if he had trusted his instincts alone, he'd have found the enemy. As it was, Villeneuve heard of Nelson's arrival and, still afraid to confront him, ran towards the Azores islands in the mid-Atlantic. Nelson once more gave chase, though this time, for a while, he could be sure they were going the right way by the trail of debris left behind by the poorly-maintained enemy ships!

Nelson was bitterly disappointed at having come so close yet so far to a major battle. But the chase hadn't been a failure - he had chased off a large enemy fleet before they could do any damage to the crucial British trade interests. He now believed that Villeneuve would go back to the Mediterranean, and so he sailed towards Gibraltar, hoping to get news there.

In the meantime, however, the

Admiralty in London had heard that Villeneuve was heading for Ferrol in

northern Spain. So Cornwallis was ordered to leave Brest and try to

intercept him, while Nelson was told to join Collingwood off Cadiz in case

Villeneuve went there.

In the meantime, however, the

Admiralty in London had heard that Villeneuve was heading for Ferrol in

northern Spain. So Cornwallis was ordered to leave Brest and try to

intercept him, while Nelson was told to join Collingwood off Cadiz in case

Villeneuve went there.

The French fleet at Brest could at this point have been a threat, but Ganteaume would not leave. Like Villeneuve, he was a survivor of the Nile, having been on the Orient which had blown up during the course of the battle. He was well aware of the superiority of the British Navy over the French, and had no intention of fighting them if he could help it. He had tried once to escape from Brest during a heavy fog, but the fog had suddenly lifted and he'd run back into port. He thought that Cornwallis' leaving had been a ruse intended to draw him out into an ambush which would destroy his fleet, and so he refused to leave. It wasn't long before any opportunity was missed, as Cornwallis' ships soon returned.

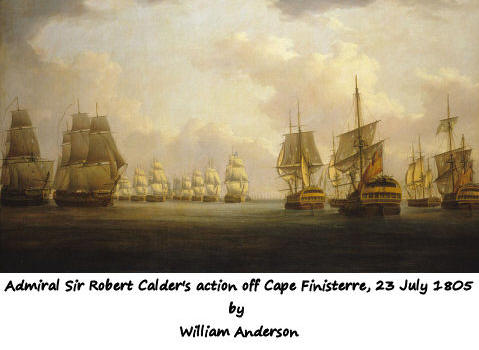

On the 22nd of July 1805, Villeneuve's fleet almost made it to Ferrol, but were intercepted off nearby Cape Finisterre by Robert Calder's fleet, which had been reinforced to 15 ships. Villeneuve at this point had 22. But although Villeneuve's fleet outnumbered Calder's, they had just made a long, difficult Atlantic crossing, so the men were tired, some ships had been damaged by bad weather, and they were short on stores.

| Calder | Villeneuve - (F) = French ship, (S) = Spanish |

| Agamemnon (64), Capt. John Harvey | (F) Achille (74), Comm. Louis-Gabriel Denieport |

| Ajax (74), Capt. William Brown | (F) Aigle (74), Comm. Pierre-Paulin Gourrege |

| Barfleur (98), Capt. George Martin | (S) America (64), Comm. Juan Durrac |

| Defiance (74), Capt. Philip Durham | (F) Algeciras (74), Rear-Admiral Charles Rene Magon de Medine, Comm. Gabriel-Auguste Brouard |

| Dragon (74), Capt. Edward Griffith | (S) Argonauta (80), Admiral Federico Gravina, Comm. Rafael de Hore |

| Glory (98), Rear-Admiral Charles Stirling, Capt. Samuel Warren | (F) Berwick (74), Comm. Jean-Gilles Filhol de Camas |

| Hero (74), Capt. Alan Hyde Gardner | (F) Bucentaure (80), Admiral Pierre-Charles Villeneuve, Comm. Jean-Jacques Magendie |

| Malta (80), Capt. Edward Buller | (S) Firme (74), Comm. Rafael de Villavicencio |

| Prince of Wales (98), Admiral Robert Calder, Capt. W. Cumming | (S) Espana (64), Comm. Bernardo Munoz |

| Raisonnable (64), Capt. Josias Rowley | (F) Formidable (80), Rear-Admiral Pierre Dumanoir |

| Repulse (64), Capt. Arthur Kaye Legge | (F) Indomptable (80), Comm. Jean Joseph Hubert |

| Thunderer (74), Capt. William Lechmere | (F) Intrepide (74), Comm. Louis Infernet |

| Triumph (74), Capt. Henry Inman | (F) Atlas (74) |

| Warrior (74), Capt. Samuel Hood Linzee | (F) Mont Blanc (74), Comm. Guillaume Lavillegris |

| Windsor Castle (98), Capt. C. Boyles | (F) Neptune (80), Comm. Esprit-Tranquille Maistral |

| (F) Pluton (74), Comm. Cosmao-Kerjulien | |

| (S) San Rafael (80), Comm. Francisco de Montes | |

| (F) Swiftsure (74), Comm. Charles Villemadrin | |

| (F) Scipion (74), Comm. Charles Berrenger | |

| (S) Terrible (74), Comm. Francisco Mondragon |

The two fleets saw each other in

late morning. Villeneuve intended to attack the British ships, but the

winds were so light that it took all day to get close enough, and he decided

not to initiate a battle.

The two fleets saw each other in

late morning. Villeneuve intended to attack the British ships, but the

winds were so light that it took all day to get close enough, and he decided

not to initiate a battle.

But as it was, Calder's fleet, led by Captain Gardner in the Hero, attacked Villeneuve's line in the early evening. But the battle quickly descended into a confusing melee, as the combination of fog and failing light meant that visibility was poor. The Malta, Captain Buller, was last into battle, but suddenly found herself surrounded by five enemy ships. She fought fiercely, firing from both sides, and eventually forced the Spanish San Rafael to surrender and sent a boarding party to take the Spanish Firme.

Three hours in to the battle, as darkness fell, Calder signalled to discontinue the action, but some ships continued to fire for another hour in the confusion. He intended to continue the action the next day, but even though the enemy superiority in numbers was now two ships less, he instead decided to protect his two prizes. The fleets stayed close for two days, until Villeneuve turned south, and Calder took his prizes north-east. But Calder failed to prevent Villeneuve from joining with the Ferrol fleet, and the new fleet of 29 enemy ships headed south for Cadiz - though Villeneuve's orders had been to go to Brest, he was wary of a superior British fleet.

Furious at his incompetent Admiral, Napoleon later said,

"Gravina [the Spanish Admiral] is all genius and decision in combat. If Villeneuve had had those qualities, the battle of Finisterre would have been a complete victory."

And, on another occasion,

"If Admiral Villeneuve, instead of entering Ferrol, had contented himself with rallying at the Spanish squadron, and had sailed for Brest to join Admiral Ganteaume, my army would have landed; it would have been all over with England."

As it was, Napoleon recognised that this battle signified the end of his hopes of invading England. He renamed his Armee d'Angleterre to the Grande Armee, and marched off to fight Russia and Austria instead.

Despite this, Calder was heavily criticised for not continuing the battle, and ended up demanding a court-martial to clear his name. Nelson was later ordered to send him home. Though he had not particularly liked Calder previously, and Calder's actions in leaving off battle contradicted everything Nelson believed about warfare, he took pity on him, and granted his request to return to England in his flagship, the Prince of Wales, rather than a frigate. This was a 98-gun ship-of-the-line, and as such was desperately needed in an imminent battle in which the British were already outnumbered. But Nelson's humanity compelled him to allow his fellow Admiral to return home with some degree of dignity.

Both Admirals, Calder and Villeneuve, had failed in their objectives. But while Calder had at least taken two prizes, Villeneuve had effectively retreated, forcing Napoleon to abandon his whole plan. It could also be argued that as Calder had left the French fleet two ships weaker, and repelled Villeneuve from the direction of England, he hadn't entirely failed. Nevertheless, the court-martial resulted in Calder being severely reprimanded for not attempting to continue the action, but he was at least acquitted of cowardice.

Meanwhile, Nelson had overtaken Villeneuve before the battle, joined Collingwood off Cadiz, and then waited at Gibraltar for news. They hadn't heard about Calder's attack, and still didn't know where Villeneuve was - Collingwood believed that by now, he would be at the Channel.

Poor old Nelson was still unwell, and increasingly depressed as he hadn't won the great battle he'd hoped and planned for. It was as if the last two years of constant, monotonous and at times difficult blockade, had been for nothing. Finally, the Admiralty ordered him home. After one final defiance of orders, distributing his ships as he saw fit to protect his beloved Mediterranean, Nelson and Victory went home. They were both in need of some TLC.

On the bright side, of course, Nelson was now able to return home to 'dear, dear Merton', with his beloved Emma and their young daughter. But he wasn't able to spend as much time there as he would have liked. His time was spent mostly in London, split between the Admiralty, the Navy Board, and discussions with the Prime Minister William Pitt, who he had grown close to, offering his expert knowledge and advice. With that, and near constant visits from family, friends and colleagues, Nelson and Emma had very little time alone together at all during the short time Nelson was home.

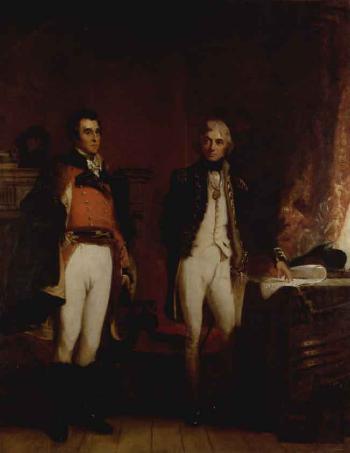

In September 1805, Nelson visited the Colonial Office for a meeting with the Secretary of State, Lord Castlereagh. Castlereagh was running late, and as Nelson waited outside the office, Sir Arthur Wellesley, who would later become the great Duke of Wellington, came in. As they waited, they chatted about Sir Robert Calder's battle of Cape Finisterre, the news of which had just been received. Wellesley obviously recognised Nelson - by this time quite famous, his image plastered over memorabilia and celebrated as a hero, the one-armed little admiral most likely dressed in uniform would have been hard not to recognise. But Nelson evidently did not recognise Wellesley - he had only recently returned from India, and with his campaign being so far from home, he wasn't yet so well-known. Because of this, Nelson's awkwardness led to a conversation which Wellesley later described as,

"...almost all on his side and all about himself and, in reality, a style so vain and so silly as to surprise and almost disgust me."

As they spoke about Calder's indecisive action, Wellesley said, "This measure of success won't do nowadays, for your Lordship has taught the public to expect something more brilliant."

Soon after this piece of flattery, Nelson went out of the room to find out who it was that he was speaking with. Returning with that knowledge, he started up the conversation again almost as a different person. He now knew who was speaking with, someone who already knew of him, and had actually already corresponded with while Wellesley had been in India. Now comfortable with his companion, he could relax, and for almost two hours while Castlereagh kept them writing, they spoke of affairs both in England and abroad. At one point Nelson asked Wellesley if he would lead troops to occupy Sardinia, to which Wellesley replied that he would rather not as he had only just returned from India. Wellesley's lasting impression of Nelson and their conversation was:

"I don't know that I ever had a conversation that interested me more. Now, if the Secretary of State had been punctual... I should have had the same impression of a light and trivial character that other people have had, but luckily I saw enough to be satisfied that he really was a very superior man; but certainly a more sudden or complete metamorphosis I never saw."

Next - The Countdown to the Battle

Copyright Vicki Singleton 2013.