|

|

|||

The Battle of Trafalgar was the most decisive, and the last, major Naval battle in English history. In it, Lord Nelson achieved the glorious victory over the French he had so dreamed of, and ended the French threat to his King and Country. It was also where he met his destiny.

The Trafalgar Campaign: The Long Blockade of Toulon.

In

May 1803, the Napoleonic War began. Peace talks between England and

France broke down because Napoleon would not back down on demanding

possession of Malta. The island was strategically important, and for

the English Navy was almost the only base for supplying and refitting a

Mediterranean fleet. Napoleon also threatened Egypt, and British

interests in India. Not only that, but he had an army hovering at

Boulogne, just across the English Channel, threatening to invade - though,

that threat wasn't particularly serious. He'd been there for a while,

and while commanding the Channel Fleet Nelson had had a poke at the French

fleet in harbour. It hadn't been a particularly successful attack by

any means, but it had shown Napoleon that the British would not stand for

his nonsense.

In

May 1803, the Napoleonic War began. Peace talks between England and

France broke down because Napoleon would not back down on demanding

possession of Malta. The island was strategically important, and for

the English Navy was almost the only base for supplying and refitting a

Mediterranean fleet. Napoleon also threatened Egypt, and British

interests in India. Not only that, but he had an army hovering at

Boulogne, just across the English Channel, threatening to invade - though,

that threat wasn't particularly serious. He'd been there for a while,

and while commanding the Channel Fleet Nelson had had a poke at the French

fleet in harbour. It hadn't been a particularly successful attack by

any means, but it had shown Napoleon that the British would not stand for

his nonsense.

This would be a total war, and a decisive one. To win, Napoleon would have to invade England. To win, the British would flex their Naval muscles and destroy the French fleet - because without ships, how could anyone reach the little island? Superiority at sea would also give Britain control over trade, and so they could throttle the French economy.

And who better to lead the British Navy to achieve this superiority in the Mediterranean? Nelson of course! He was promoted to Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean, and sailed out there in the Victory, arriving in July 1803.

Nelson's fleet was not, of course, the only British presence at sea. George Elphinstone (Lord Keith) was in the North Sea and William Cornwallis was in the Channel, blockading the French fleet at Brest. Napoleon technically had a larger fleet than Britain, but it was scattered. Because of Cornwallis' Channel Fleet, Napoleon was stuck at Boulogne, and the only way he could cross the Channel would be to pull his fleet together and destroy the British there. The French fleet in Toulon, south of France, was the biggest threat, but rather than attempt to cage it in so it couldn't reach the Channel, Nelson intended to lure it out and destroy it.

Nelson

sailed in the Victory as far as Cornwallis' fleet, and left her there

in case Cornwallis wanted her, continuing to the Mediterranean in HMS

Amphion, a frigate captained by his old friend, Thomas Hardy.

Cornwallis, of course, would not keep one of England's finest ships from

Nelson, and sent her on after him, captained by Samuel Sutton. On 30th

July she caught up with Nelson, who had joined the squadron under his

second-in-command, Richard Bickerton, and he boarded her, taking Hardy with him

and giving Sutton the Amphion.

Nelson

sailed in the Victory as far as Cornwallis' fleet, and left her there

in case Cornwallis wanted her, continuing to the Mediterranean in HMS

Amphion, a frigate captained by his old friend, Thomas Hardy.

Cornwallis, of course, would not keep one of England's finest ships from

Nelson, and sent her on after him, captained by Samuel Sutton. On 30th

July she caught up with Nelson, who had joined the squadron under his

second-in-command, Richard Bickerton, and he boarded her, taking Hardy with him

and giving Sutton the Amphion.

From then on, Nelson was acting virtually on his own. The objectives given to him from London were to, obviously, destroy the Toulon fleet. He had to protect Egypt, Turkey and Naples, and protect British trade. He was also to keep an eye on what the Spanish were up to, and prevent them from joining the French fleet if they decided to join the war.

In December 1803, Nelson wrote to Earl St. Vincent, saying;

| The station I chose to the Westward of Sicie was to answer two important purposes: one to prevent the junction of a Spanish Fleet from the Westward; and the other to be to windward so as to enable me, if the Northerly gale came on to the NNW or NNE, to take shelter in a few hours either under the Hieres Islands or Cape St Sebastian, and I have hitherto found the advantage of the position. Now Spain having settled her Neutrality, I am taking my winter's station under St Sebastian to avoid the heavy seas in the Gulf, and keep Frigates off Toulon. |

But although Nelson kept a dutiful eye on the Spanish preparations for war, he wasn't overly concerned. He knew that although the Spanish fleet had some fine, majestic ships, the navy itself was weak. They lacked funds due to having to pay so much to Napoleon; a yellow fever outbreak had killed many seamen, who were not replaced; stores were short. It was also well-known that the discipline and gunnery skill of the Spanish seamen was far inferior to the British. In September 1803, Nelson wrote to Major-General Villettes in Malta, saying;

| From our communication with Spain, it looks rather hostile, she must go to War either with France or us, and all the blame is laid at our door because we will not bow to France and allow the world to be at peace. |

and pragmatically added;

| I want Peace and therefore if we are to have more Powers upon us, the sooner they begin the better, and not give us a long War. |

Also in September, in a letter to Emma Hamilton, he wrote;

| However by management I have got supplies from Spain and also from France, but it appears that we are almost shut out from Spain, for they begin to be very uncivil to our Ships. |

In November, he wrote dismissively of a Spanish war, to Alexander Ball;

| Captain Swaine was at Barcelona on October 13th, therefore I do not think a Spanish War so near. We are more likely to go to War with Spain for her complaisance to the French, but the French can gain nothing but be great losers by forcing Spain to go to War with us, therefore I never expect that the Spaniards will begin unless Buonaparte is absolutely mad, as many say he is. |

He then, in a way which I find quite funny, went on to mock Napoleon's efforts at an invasion of British shores;

| What! he begins to find excuses! I thought he would invade England in the face of the Sun! Now he wants a three-days' fog, that never yet happened! and if it did, how is his Craft to be kept together? He will soon find more excuses or there will be an end of Buonaparte, and may the Devil take him! |

Correspondence often took weeks to reach Nelson from London - sometimes longer if a dispatch ship was captured - and so he had to make a lot of decisions for himself and be self-sufficient. He had to organise intelligence networks and establish supply contacts, keep his ships in order and his men healthy. It may have seemed an intimidating prospect, but Nelson was in his element. This was what he had always wanted - total command of a large fleet in the most important station, preparing to annihilate the enemy.

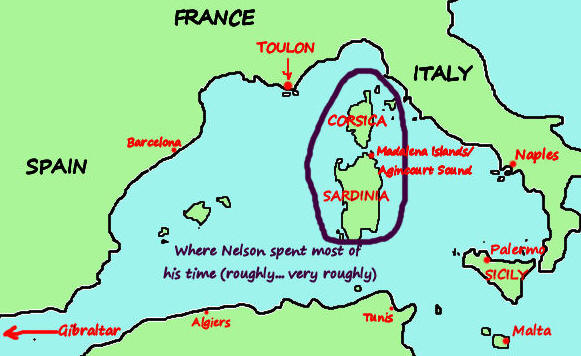

Nelson based himself at Sardinia. There, he was best positioned to block any French attempt to go east to Egypt, Turkey or Naples. Though Naples remained neutral (see Nelson's journal entry for July 26th 1803 for his opinion on Naples' neutrality), there was a French army there, and from there it was easy to cross to Sicily. Nelson was determined to prevent that from happening as Sicily supplied Malta, and planned to take troops there from Malta if he had to. His resolve to prevent them from getting to Egypt stemmed from his concern that from Egypt it would be easy to get to India.

Nelson also knew it was important to capture any

French merchant ships and block trade. Not only would this put

pressure on France, but would help persuade other countries such as Austria

and Russia, to ally with Britain. It was also necessary, for obvious

reasons, to stop any transport ships from carrying French troops off the

mainland.

As for his primary objective, the destruction of the Toulon fleet - Nelson played games of cat and mouse with them. Rather than closely blockade them a la Cornwallis, he kept his fleet just out of sight. Almost every day he'd send a frigate in to have a look at what they were doing. He hoped that because the French wouldn't know exactly where he was, or the size of his fleet, they would be lulled into a false sense of security, and sail when the wind was favourable. His letters throughout the period tell of his daily expectation of their appearance. To win, he would out-think, out-manoeuvre, and out-fight his enemy.

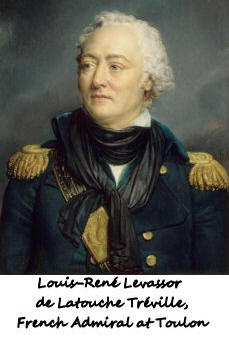

But the French were cautious, and Nelson knew that they would not risk fighting unless they had to. In twenty-two years of war, there had only been six major battles between England and France, and only two of those had been decisive. Nelson had been present at both of them, and had of course commanded at the Nile. The French Admiral at Toulon, Latouche Treville, like any admiral, knew what Nelson was capable of - though it had been he who had repelled Nelson's attack on the fleet at Boulogne in 1801. Nelson planned to lure the French into poking their heads out of Toulon, by making them think his fleet was inferior. He didn't want to fight them too close to shore, as that ran the risk of them being able to run away from him and knowing the strength of his fleet. But Latouche Treville climbed to the highest point in Toulon every day to watch out for the English. He wasn't prepared to face the Admiral who had wiped out the Nile fleet until he had definite orders from Napoleon, which he did not.

From the outset, Nelson's time as Commander-in-Chief was beset with problems, but he dealt with them all remarkably. One that he complained about often in his letters to the Admiralty was the condition of his ships. Victory had just had a refit in England before he took her to the Mediterranean, and he was happy with her, Canopus, Donegal, and Belleisle. But on the 24th of August, he wrote to Henry Addington about the poor condition of the Triumph, Superb, Monmouth, Agincourt, Kent, Gibraltar and Renown, and that he wished them back in England for a complete refit. They needed constant maintenance, which was difficult so far from England and with very few suitable ports available to Nelson. The Admiralty expected him to use Malta, but he was disdainful of it, as it was too far away. So he kept his battleships together, and only sent his frigates to look into Toulon almost daily.

The ships that Nelson had with him at this time were:

|

Active (38-gun frigate) |

Captain Richard Mowbray |

|

Agincourt (64 guns) |

Captain Charles Schomberg |

|

Amphion (32-gun frigate) |

Captain Samuel Sutton |

|

Belleisle (74 guns) |

Captain John Whitby |

|

Donegal (74 guns) |

Captain Richard Strachan |

|

Gibraltar (80 guns) |

Captain George Ryves |

|

Kent (74 guns) |

Rear-Admiral Richard Bickerton; Captain Edward O'Bryen |

|

Monmouth (64 guns) |

Captain George Hart |

|

Phoebe (36-gun frigate) |

Captain Thomas Capel |

|

Renown (74 guns) |

Captain John Chambers White |

|

Superb (74 guns) |

Captain Richard Goodwin Keats |

Despite his despair at the condition of many of these ships, in the same letter Nelson wrote that they were 'amongst the very finest Ships in our Service - the best commanded and the very best manned'. The Admiralty, however, were not forthcoming with ships to replace them. Nelson was nonetheless determined to keep his fleet at sea as long as his ships could withstand the weather.

And therein lay another problem - the weather. In his journals for this period, Nelson wrote almost daily of squalls and storms. For a man who suffered from sea-sickness as he did, this was a nightmare. Some days, his entry consisted only of a note of the weather - perhaps his sickness kept him from writing more! He wrote often to Emma, and anyone else who would listen, that he felt unwell all the time. Still, he vigilantly kept a log of the weather, sometimes twice a day, as well as recording it in his private journal. He hoped that his knowledge of the weather in the area would give him an advantage over the French.

Another thing that Nelson complained about almost constantly was his lack of frigates, which he called his 'eyes'. He needed them to look into Toulon, and for other reconnaissance missions. Before the Battle of the Nile, the lack of frigates had caused him severe problems - it would do the same here, too.

Nelson's fleet was the same size as the French one in Toulon, so he couldn't afford to send any of his ships-of-the-line to any port for supplies. So he arranged for store ships to travel between the ports and his fleet. This might seem an obvious solution, but it wasn't common practice at the time. He set up reliable supply networks at various ports around the Mediterranean, one important one being at Roses in Spain. His contact there, Mr Gayner, was a British wine merchant, and also provided Nelson with onions and beef. He also established good intelligence networks in Spain, and elsewhere, and so didn't need to waste ships by having them watch the ports there. He also got lucky in managing to capture a French ship which had documents, charts and signal codes.

For the next two years, Nelson achieved an impressive yet underestimated feat. He kept a fleet of damaged ships together, well-supplied, and as well-maintained as they could be. His aim was always to keep his ships with five weeks' worth of supplies, so they were ready to leap into a long chase of the French at a moment's notice.

He of course also had to keep the men who manned his ships in working order. When he first boarded the Victory, he complained about the inexperience of most of the crew. But during the time of the blockade, the crews of all his ships were drilled every day. They were also, considering the length of time they went without setting a foot on shore, remarkably healthy, at times with not a single man ill. This meant that they were ready for all eventualities - to chase, to fight, or to continue at sea. On October 8th, Nelson wrote to Hugh Elliot saying;

| Never was health equal to this Squadron. It has been within ten days of five months at sea and we have not a man confined to his bed, therefore if these fellows wait till we are forced into Port they must wait some time. |

Nelson knew first-hand the effects of illness such as scurvy - he had lost almost all his upper teeth because of it - and so he did his utmost to prevent it, doing whatever he could to procure fresh food, particularly lemons and onions which were known to help.

It was also imperative to keep up morale among the crews and officers, and to inspire loyalty in them. In this, Nelson excelled. He rotated which ships he sent on reconnaissance missions, thus reducing boredom which would easily set in while languishing on a ship in the middle of the ocean. He also made a point of spending time with officers, even midshipmen, entertaining them onboard the Victory. In this way, he would get to know them, and they him. They found him to be kind, accessible, and a pleasure to serve under. As they grew to know him, they grew to love him, and he gained their trust, loyalty and confidence. This was essential to his style of leadership, and was what set him apart from other admirals.

But while the health of the fleet as a whole was exceptional, the same could not be said for poor Nelson himself. The anxiety and stress of such a command took its toll - other than the constant sea-sickness, he slept little and erratically, and his eyesight suffered as a result of constant writing and reading of letters and reports. On December 14th 1803, he wrote to his brother, William;

| ...but next Christmas, please God, I shall be at Merton; for, by that time, with all the anxiety attendant on such a Command as this, I shall be done up. The mind and body both wear out, and my eye is every month visibly getting worse, and I much fear it will end in total blindness. |

And earlier that year, in October, he had grumpily written (to an unknown recipient);

| Our gales of wind are incessant and you know that I am never well in bad weather, but patience I hope will get me through it... I am at this moment confoundedly out of humour. |

He was physically, mentally, and emotionally exhausted, and needed not just a rest, but a pick-me-up from the public praise he received when in England. Nelson did apply for sick leave, and wrote to Emma more than once telling her he would be home soon. But, even when granted leave, he didn't take it. He was worried that if he left, he might be permanently replaced. More importantly than that, he could not be satisfied with what he had achieved unless it culminated in the destruction of the enemy he had stalked for so long.

Next - The Chase of Villeneuve -->

Copyright Vicki Singleton 2013.