|

|

|||

| The Trafalgar Campaign: The Long Blockade of Toulon |

| The Trafalgar Campaign: The Chase of Villeneuve |

| (This Page) The Trafalgar Campaign: Countdown to the Battle |

| Trafalgar: Nelson's Final Battle |

| The Death of the Hero |

| Trafalgar: The Aftermath and the Hurricane |

The Trafalgar Campaign: Countdown to the Battle

Read Nelson's private diary from the day he boarded Victory, to the day of the battle

Villeneuve and his fleet were now blockaded in Cadiz by Vice-Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood. But that didn't mean he didn't pose a threat. Though some of the French ships and crew were in poor condition after the long chase to the West Indies and back, they still outnumbered the British. And if they escaped, they could still damage British trade convoys from the West Indies, and stop British troops from meeting with the Russians to take back Italy. Napoleon had given up his designs on an invasion of Britain and turned for Austria, but the French naval threat had to be neutralised completely.

And so it was that Admiral Horatio Nelson was sent once more to his post as Commander-in-Chief. No other officer could have the skill, knowledge and genius required to totally annihilate the enemy.

Before leaving Merton, his paradise, Nelson knelt at his daughter's bedside as she slept, and said a prayer for her. Elegantly dressed in full uniform, complete with his honours and medals, he rode in a carriage to Portsmouth. On the way there, he wrote the following prayer - somewhat brooding and melancholy, yet also with strong undertones of his determination to do whatever his duty demanded of him:

| Friday night at half past

Ten drove from dear dear Merton where I left all which I hold most dear

in this World to go to serve my King & Country. May the Great God

whom I adore enable me to fullfil the expectations of my Country and if

it is his good pleasure that I should return my thanks will never cease

being offered up to the Throne of his Mercy. If it is his good

providence to Cut short my days upon Earth I bow with the greatest

Submission relying that He will protect those so dear to me that I may

leave behind. His will be done Amen Amen Amen The National Archive, catalogue reference PROB 1/22 |

It was not the first time he had foreseen his death in battle. In fact, he hoped for a glorious death in a victorious battle. But this poignant diary entry is different. It is not a dramatic declaration like those he had previously made in letters to friends and family, which were probably composed of phrases that he hoped would memorable as his 'famous last words'. This is a private prayer to his God, and yet also a plea. He was still willing to die in the name of his duty but, perhaps because he had found such contentment with his wife in all but name, and his daughter, he rather hoped he wouldn't have to.

Resting at an inn at Portsmouth, he finished dealing with other private business. He then made his way to board the Victory, taking backstreets so as to avoid the pressing crowds that had gathered to see their hero. He 'embarked at the Bathing Machines', a little way from the dock, but was still seen off by a large crowd of people. He was then rowed out to the Victory with his Captain, Thomas Hardy. As they left, he turned to Hardy and quietly said, "I had their huzzahs before. I have their hearts now." That public sentiment was something he cherished.

Emma was never far from his mind, and as early as the 17th, as he stopped at Plymouth to pick up the Ajax and Thunderer, he was writing to her:

| I intreat, my dear Emma, that you

will chear up; and we will look forward to many, many happy

years, and be surrounded by our children's children. God

Almighty can, when he pleases, remove the impediment. My heart and soul is with you and Horatia. The Letters of Lord Nelson to Lady Hamilton, anon. |

He wrote to her several more times after that.

On the 25th of September, he heard that the enemy had not left Cadiz and, happily noting it in his journal, optimistically wrote, "therefore I yet hope they will wait my arrival." He didn't want a battle to happen without him! On the 26th he sent the Euryalus to tell Collingwood that he was ready to take command, and on the 28th he and Victory joined the fleet.

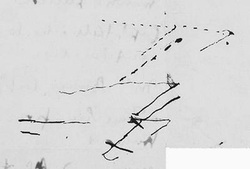

Nelson explaining his plan to his captains.

Upon reaching the fleet, Nelson became occupied with setting up look-out ships, formulating strategies, and general administration. A small squadron under Rear-Admiral Thomas Louis in the Canopus joined on the 1st of October, and was promptly sent back out to Gibraltar to get supplies. Louis strongly protested, believing he would miss the battle, but Nelson assured him that he would be back before the enemy got out. But he was wrong, and Louis and his squadron did indeed miss the battle, to Louis' intense disappointment.

Collingwood in the Royal Sovereign joined on the 8th, and on the 9th Nelson sent him what he called the 'Nelson Touch'. This was the essence of his strategy in the upcoming battle. Flying in the face of traditional battle strategy, whereby a fleet would line up parallel with an enemy line and fire broadsides on each other, normally in one-on-one encounters, Nelson's strategy involved sailing in two columns. One would characteristically be led by him, the other by Collingwood, and they would sail directly into the enemy line, cutting right through it. This would decrease the enemy's advantage of numbers, as the front ships of their line would be rendered ineffective until they were able to turn around and re-join the battle, during which time the British fleet would outnumber and pummel the remainder.

This is Nelson's sketch of his battle plan, which he drew while explaining it to his captains. The thick diagonal line represents the enemy line. You can see how hard Nelson pressed his pen into the paper while excitedly explaining the two 'cuts' his fleet would make in the line. You can read a more detailed explanation of the sketch at the National Maritime Museum site.

This strategy was incredibly risky. The ships at the front of the British columns would be vulnerable to enemy broadsides and would take quite a beating before even reaching them. Nelson placed his strongest ships, Victory and Royal Sovereign, at the head of the columns as they would be more able to withstand the attack, but it posed a huge risk to him personally. But, apart from his character being unable to do anything other than lead, he knew that his presence at the forefront of the attack would inspire his men and boost their morale and confidence. They would have to demonstrate nerves of steel, as they would not be able to do any effective damage and so would be ordered to hold fire until the line was broken. Nelson's vision was of a 'pell-mell battle', as he had earlier described it, surprising the enemy with an all-out melee that was entirely dependent upon the superior, faster and more accurate gunnery and higher morale of his well-trained, highly disciplined men. He also put complete faith in his captains, telling them to choose their own targets and trusting them not to need signals from him, as in the confusion of a melee, signals could easily be misread or not even seen at all. He simply said that "No captain can do very wrong if he places his ship alongside that of an enemy." In the ensuing chaos as the enemy line was torn apart, it would be every ship for itself. His ability to fully trust his captains had been successful at the Nile, and it would prove to be again.

Nelson was ecstatic with the response his strategy received. He wrote to Emma,

| ...when I came to explain to them

the Nelson touch, it was like an electric shock.

Some shed tears, all approved - "It was new, it was singular, it

was simple!" and, from Admirals downwards, it was repeated - "It

must succeed, if ever they will allow us to get at them!

You are, my Lord, surrounded by friends whom you inspire with

confidence." The Letters of Lord Nelson to Lady Hamilton, anon. |

And that, really, was the key. His complete faith and confidence in his officers instilled them with the kind of self-belief that enabled them to achieve a potential that could not be reached by simply waiting for, and acting upon, orders from their commander.

Nelson's favourite ship, the Agamemnon, joined the fleet from England on the 13th having 'had a narrow escape from capture' by a small French squadron off Cape Finisterre. L'aimable also joined after having a similar such escape. On the same day, Nelson wrote simply that 'Prince of Wales sailed for England'. The Prince of Wales was a big 98-gun ship-of-the-line, and though desperately needed by Nelson and his outnumbered fleet, she carried Vice-Admiral Robert Calder back to England. He was to be disciplined for his failure to everything in his power to attack the French fleet in the indecisive Battle of Cape Finisterre back in July, and he asked Nelson if he could take his flagship rather than a frigate. Nelson took pity on him and granted his requested, depriving himself of a valuable ship but allowing a fellow Admiral to return home with some dignity.

It was of course important to keep a close eye on the French, but Nelson wanted to keep the bulk of his fleet out of sight of Cadiz so Villeneuve wouldn't have an exact idea of how many ships he had. So he placed several frigates - which he had always called his 'eyes', and valued highly - close to the harbour mouth. Rather than have to wait for one to run back to him and tell him if the enemy made sail, he put the Defence (74 guns) and Agamemnon (64 guns) 7-10 leagues west from Cadiz, and then Mars (74 guns) and Colossus (74 guns) between them and him, writing in his diary, 'by this Chain I hope to have a constant communication with the frigates off Cadiz'. He would not again make the mistake of letting Villeneuve evade him, and on the 16th he was 'Employd forming the fleet into the order of Sailing'. Not only would the French fleet be unable to evade him, he would be ready for them when they tried.

Meanwhile, at the Combined Fleet...

Admiral Villeneuve, commander of the combined fleets of France and Spain, was not having an easy time of it. He was not confident of success in the upcoming battle. He knew that Nelson had joined the British fleet and, being a Nile survivor, he knew exactly what Nelson was capable of. He also knew, from first-hand experience, that the British possessed better guns, with less recoil, better gunpowder, and their crews were far quicker and more accurate with those guns than the French.

Morale within the Combined Fleet was also bad. The French and Spanish seamen didn't get on, and would get into fights. Even the captains argued over what to do. Villeneuve attempted to go some way to solving the problem by mixing up the French and Spanish ships in the line, so glory and blame would be shared equally, and they'd be less likely to desert each other. But it didn't help that his only real achievement had been escaping from the Battle of the Nile with 4 ships, and even then he'd been captured later on. So the Spanish thought him incapable of leading a major action. Morale was extremely low.

Villeneuve received orders from Napoleon to sail for Naples, but decided that his best chance of evading Nelson's blockade was to wait for a favourable wind. But two days later, he suddenly changed his mind and decided that they should sail right away. He'd heard that Napoleon, not realising that his orders were impossible - he didn't have much concept of naval warfare compared with that on land - and believing Villeneuve to be a coward, was sending his replacement. Villeneuve would rather die with honour in battle than have his reputation destroyed by Napoleon's insistence that he was cowardly.

'at 1/2 pt: 9', wrote Nelson on the 19th of October, 'the Mars being one of the look out Ships made the Signal that the Enemy were coming out of Port made the Signal for a general Chase SE.'

Nelson's 'chain of communication' had worked. His frigates had seen Villeneuve leave Cadiz, and the signal had got back to him quickly. Still, he had to move fast to make sure the French weren't able to get either out into the open Atlantic as they had before, or retreat to the westwards and Toulon. He also didn't want them to get the chance to escape back into Cadiz. To make sure his approach was as fast as possible, he let his fastest ships go ahead during the night, carrying a light, and 'for the Britannia Prince & Dreadnought they being heavy sailers to take Stations as Convenient.'

On the 20th, he kept up the chain of communication and continued to rely on his frigates. 'In the afternoon,' he wrote, 'Captain Blackwood [in the Euryalus] telegraphed that the Enemy seemed determined to go to the Westward; and that they shall not do if in the power of Nelson and Bronte to prevent them'. By 4am on the morning of the 21st, Nelson's fleet were standing towards a French fleet who were manoeuvring to meet them. He was so pleased with the chain of communication that he wrote, 'The frigates and Look out Ships kept sight of the Enemy most admirably all night and told me by Signals which tack they were upon.'

Villeneuve knew what Nelson's attack plan was likely to be, and the orders he gave to his captains were similar; that they should act on their own initiative, but ensure that they were always beside an enemy ship. But Nelson had been instilling his captains with this ideal for months, whereas the French and Spanish were still used to the idea of parallel lines of battle. So Villeneuve's only option was to form the line he knew Nelson was expecting.

He planned for his line to contain three divisions, each led by separate admirals, in pre-determined positions. But because these positions were not the same as their order of sailing, they had to spend time trying to manoeuvre into them. Because there was a heavy swell, but very little wind, it took them a long time to get into position, so Villeneuve ordered them to turn into the wind. However, this required some skill on the part of the captains, and so the ships turned at different speeds. Faster ships had to turn out of the line to avoid collision, creating gaps in the line, and the reserves, which should have been to the west of the line so they could see where help was needed, ended up at the rear. Villeneuve could only watch as the organised, disciplined two columns of British ships marched sedately and purposefully towards his disorganised line.

Nelson's Last Letters and Diary Entry, and the 'Trafalgar Prayer'

With barely any wind, the approach to the enemy line was painfully slow. All preparations for battle were made and the decks were cleared, and the men still had time to prepare their guns, eat, and write their wills. Nelson's cabin had been cleared and all his furniture pushed out of the way. Kneeling on the floor, he found time to write his last diary entry, which included what has become known as his 'Trafalgar prayer':

|

Monday Oct 21st 1805 At day light saw the Enemys Combined Fleet from E to ESE bore away made the Signal for order of sailing and to prepare for Battle the Enemy with their heads to the Southward, at 7 the Enemy wearing in succession, May the Great God whom I worship Grant to my Country and for the benefit of Europe in General a great and Glorious Victory, and may no misconduct in any one tarnish it, and may humanity after Victory be the predominant feature in the British fleet, for myself individually I commit my Life to Him who made me, and may his blessing light upon my Endeavours for serving my Country faithfully. To Him I resign myself and the just cause which is Entrusted to me to Defend. amen, amen, amen. |

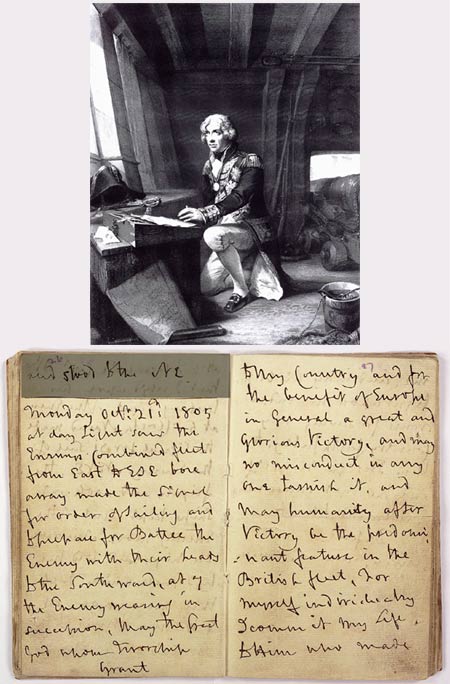

Below is an artist's impression of Nelson praying, and a photo of his diary.

He followed this with a codicil to his will, which was witnessed and signed by Captains Hardy and Blackwood.

| October the Twenty first one thousand

Eight hundred and five then in Sight of the Combined fleets of

France and Spain distant about Ten Miles.

Whereas the Eminent Services of Emma Hamilton Widow of the Right Honorable Sir William Hamilton have been of the very greatest Service to our King & Country to my knowledge without ever receiving any reward from Either our King or Country, first that she obtain'd the King of Spains letter in 1796 to His Brother the King of Naples acquainting him of his intention to Declare War against England from which letter the ministry sent out orders to then Sir John Jervis to strike a stroke if opportunity offered against either the arsenals of Spain or her fleets. that neither of these was done is not the fault of Lady Hamilton the opportunity might have been offer'd. Secondly the British fleet under my Command could never have return'd the Second time to Egypt had not Lady Hamiltons influence with the Queen of Naples caused Letters to be wrote to the Governer of Syracuse that he was to encourage the fleet being supplied with every thing should they put into any Port in Sicily. We put into Syracuse and received Every supply went to Egypt & destroy'd the French fleet. Could I have rewarded these Services I would not now call upon my Country but as that has not been in my power I leave Emma Lady Hamilton therefore a Legacy to My King and Country that they will give her an ample provision to maintain her Rank in Life. I also leave to the beneficience of my Country My adopted daughter Horatia Nelson Thompson and I desire she will use in future the name of Nelson only. these are the only favors I ask of my King and Country at this moment when I am going to Fight Their Battle May God Bless My King & Country and all those who I hold dear my Relations it is needless to mention they will of course be amply provided for. Nelson & Bronte Wittness: Henry Blackwood T.M.Hardy

|

In this codicil was Nelson's last attempt to get the government to look after his lover and child upon his death, by reminding them of her (possibly exaggerated) value during the Nile campaign. There is just a hint of resentment in his last paragraph: 'These are the only favors I ask of my King and Country at this moment when I am going to Fight Their Battle.' Despite his willingness to give his life for his King and country, he probably knew his chance of success with this plea for a return of favours was slim, as for all her services, Emma was not his wife.

He also asked for his daughter, Horatia, to be taken care of. But here, he keeps up the pretence that she is only his adopted daughter. He and Emma, for appearances sake, had to pretend that they had adopted Horatia from a Mr and Mrs Thompson - in their story, Thompson was an officer on Nelson's ship, and Nelson wrote on his behalf, through Emma, to Mrs Thompson. After Emma's husband died, the facade slipped - not that they had been very good at keeping it up anyway. So Horatia had been christened with the name of Nelson Thompson, but now, facing his possible death, Nelson wrote a strong hint that she was, in fact, his daughter, by asking that she should drop the 'Thompson' from her name.

Two days earlier, he'd written a tender letter to her, in which he signed himself as her father for the first time:

| Victory, October 19th 1805 My dearest Angel, I was made happy by the pleasure of receiving your letter of September 19th, and I rejoice to hear that you are so very good a girl, and love my dear Lady Hamilton, who most dearly loves you. Give her a kiss for me. The Combined Fleets of the Enemy are now reported to be coming out of Cadiz; and therefore I answer your letter, my dearest Horatia, to mark to you that you are ever uppermost in my thoughts. I shall be sure of your prayers for my safety, conquest, and speedy return to dear Merton, and our dearest good Lady Hamilton. Be a good girl, mind what Miss Connor says to you. Receive, my dearest Horatia, the affectionate parental blessing of your Father, Nelson & Bronte |

Finally, Nelson wrote his last letter to Emma:

| Victory, October 19th 1805, Noon,

Cadiz, E.S.E., 16 Leagues My dearest beloved Emma, the dear friend of my bosom. The signal has been made that the Enemy's Combined Fleet are coming out of Port. We have very little wind, so that I have no hopes of seeing them before tomorrow. May the God of Battles crown my endeavours with success; at all events, I will take care that my name shall ever be most dear to you and Horatia, both of whom I love as much as my own life. And as my last writing before the Battle will be to you, so I hope in God that I shall live to finish my letter after the Battle. May Heaven bless you prays your Nelson & Bronte October 20th. In the morning, we were close enough to the Mouth of the Straits, but the wind had not come far enough to the Westward to allow the Combined Fleets to weather the Shoals off Trafalgar; but they were counted as far as forty Sail of Ships of War, which I suppose to be thirty-four of the Line, and six Frigates. A group of them was seen off the Lighthouse of Cadiz this morning, but it blows so very fresh and thick weather, that I rather believe they will go into the Harbour before night. May God Almighty give us success over these fellows, and enable us to get a Peace. |

Nelson had hoped to be able to finish the letter after the battle. But after the battle, it was found open, on his desk, unfinished.

Trafalgar - Nelson's Final Battle

Copyright Vicki Singleton 2013.